|

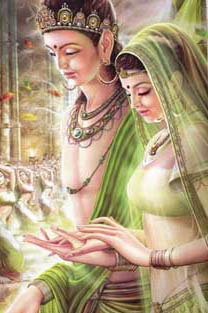

The Prince and the pain of being

The suffering of a thirty something

In

the life of every person the fourth decade has a special meaning. The

youthful formative years are definitively completed and decisive steps are

made on the path to true adulthood. That pivotal moment is recognizable in

the person of Jesus of Nazareth who preached around his thirty-third and in

the development of the Prophet Muhammad who received his revelations towards

the end of this decade. Zarathustra -ninth century bce- got his first

visions at thirty, sitting on the banks of the Himalayan river Amu Darya.

Moses -fourteenth century bce- rounded his old life at forty and became the

leader of the Jews. Based on their worldly wisdom, many people also nowadays

say that life begins at forty - often said in hindsight. Also Siddhartha

Gautama's awareness of life changed in that cardinal fourth decade. He

attained to the stage of Buddha, full enlightenment, when he was

thirty-five. Six years earlier he had secretly left his protected

environment for the first time and he was by what he saw in the world, for

the first time confronted with old age, sickness and death - he was until

then never really been aware of it. He also for the first time came into

contact with monks and he understood that they were people looking for

spiritual development, living simply and who had given away their

possessions. Then Siddhartha left his palace, wife and child, and withdrew

into the woods - traditionally the place where a Hindu goes into retreat.

After that he went to Benares to study with the renowned Alara Kalama and

later with the even more famed Uddaka. Although according to the narrations

he equalled and surpassed his teachers in a short period, of them he could

not learn how to put an end to old age, sickness and death. Religion, philosophy and the road between

Ask an

insider and he will confirm that Buddhism is not a religion. Consider the

mindset of the average Buddhist -India, Nepal, Tibet, Japan- and one might come

to the conclusion that it is a religion. A 'normal' Buddhist worships a Buddha

statue, lights incense and takes up a revering posture. He says prayers and

turns a prayer wheel, or walks around a stupa where the relics of deceased monks

are kept. However, it is true, Buddhism knows no gods and it assumes that this

is not at all possible in a world of evil and suffering. Buddhism knows no

mechanism by which the atman -the self, the soul, the consciousness- through

reincarnation can come to a higher level and after dying in a higher form of

existence - in an increasingly higher heaven as in Hindu mythology. Working on

an ever-improved form of being in Buddhism knows its reward not in an afterlife,

but in achieving a state of nirvana in physical existence - reaching that form

of being is generally achieved in several incarnations and decided upon by the

form of being of the person self. At the end of the last life a person needs to

achieve nirvana, enlightenment, when dying he reaches the state of Parinibbana,

the perfected nirvana, and the being will fall apart not longing for a new life

- samsara is brought to completion. The five khandhas of being -body, feelings,

imagination, intentions and consciousness- will disintegrate and not return

together, says the Buddha. He has always declined to give an answer to the

question, what is after the last death. He presumed this query to come forth

from metaphysical speculation by the questioner. The

central theme of existence is to find an answer to the question, what am I

doing here and why do I do it here. This is the central question of anyone at

any level expressed, at what level of consciousness whatsoever - any wording on

any level is legitimate. The Buddha has sought to raise the awareness of this

question, to remove the answering from the priesthood and to reallocate it,

giving it back to each person himself. The Buddha did not want to go any further

and could not because he was not really capable of breaking away from the

traditions of his culture, the civilization and the time where he came from.

That God disappeared from his philosophy and the existence after death also is

logical, because a God works as the causal substance of a system of punishment

and reward, while answering the essential question of life precisely concerns

what every individual does with this question - not what he thinks the desire of

the boss could be. The Buddha was a revolutionary thinker in this perspective.

He returned the responsibility for learning in life in an almost existentialist

way to every person self. Possibly this is also the reason that in many more

secular societies such as the current Buddhism has not lost its attractiveness.

Whether the Buddha has managed to demystify religion enough to make it a life

philosophy, however, remains to be seen. The four stages of enlightenment

The

two interpretations of the wisdom of the Buddha are the Mahāyāna and Theravāda.

According to the people involved Theravāda is the oldest form of Buddhism and

this interpretation will be further discussed here. The differences between the

two and further literature on Mahāyāna Buddhism are discussed in the

widely available literature. There is also stressed that these two movements are not

the result of a schism, and that the monks of the two movements without getting

any problem could stay with each other in the same convent - provided that the

rules of the monastery were respected by all. Moreover, after the death of

Siddhartha there were eight schools of which only Theravāda and Mahāyāna

prevailed. The other schools seem to have merged into one of the two, or became

extinct. The four stages of enlightenment distinguished in Theravāda Buddhism

are, Sotāpanna, Sakadagāmi, Anāgāmi and Arahant. The freeze-dried soul

The analysis Siddhartha Gautama

made of life, of the causes of pain in life -disintegration, disease and death-

is thorough and few aspects have not been considered. He brought an

elaborate system in which for the people were sufficient grounds to understand

something of life, without a need for a deus ex machina. A structure that also

wanted to offer support and comfort by clarifying that a solution to the

suffering had to come from a person self. Simultaneously there is a problem

with what he brought forward, or what is narrated by his students, it is a

system. On the one hand systematics brings a certain clarity, on the other hand

a template is created where anyone who, in this case, wants to be enlightened

will want or should even fit in. Long ago a Buddhist replied to this criticism

that beyond the stages the Buddha had analysed no relief exists. This statement

even amplified the criticism. Due also to the immutability of the dogmatic system,

Buddhism is a religion, although one without God. Or maybe saying no determinate

God is more precise. Because despite that in the philosophy of the Buddha a

pronounced God is not present, there is a cause of existence, and there must be

a cause of suffering - after all, it exists. The Buddha has never spoken about

this insight, because it would be irrelevant in attaining enlightenment - and

probably is. Besides all objections, the methodology of the Buddha makes a high level

of ostrich behaviour possible. Suffering is an inexorable aspect of life. It

cannot be dissolved as an unwelcome pest by brushing it aside or by meditating.

One endures and lives through the suffering with the specific intention to

reduce it and understand the why of it - not by cancelling the drama. The solution to

suffering indeed does not come from the outside -Jesus, the Buddha and the like-

but from within, however, not by sublimating the pain inside or freeze-drying it

there, for that is what the Buddha asks of you to do. The middle and the midpoint Yet another dimension for contemplation is the following. Siddhartha was a child of his time. With this is meant that his arguments and theories could only take place with himself and his origins as a background. In that context, he felt the need to preclude some of his attributes, to cure or to lose them - characteristics that according to him stood in the way everlasting bliss. This reveals a setting and a background in which man has to unlearn things, a culture in which man is seen as basically malevolent, or at least as limited - a very particular view on humanity. The Buddha makes recommendations for exercises to relieve suffering and prevent future suffering. A person must unlearn aspects in himself and learn other qualities. While many recommendations of the Buddha are still recommendable, for they are universal to humans, they still remain the recommendations as concluded by one human being - with many imitators, but that means nothing. His recommendations -this is important- are the instruments to reach the mind and to transform a person from the outside in. Mankind must be changed as the Buddha will have it, and not as mankind would have it. The Buddha formulated the criteria and not man found his points of change. It is as if the Buddha wants to rid an ugly and dull utensil, such as a vase, of its impurities, wants to restore the necessary spots and add properties to it, then to say that the soul of the object can now come to perfect expression. It may well be so, but nowhere the voice of the vase has sounded. It is the voice of the outsider, the Buddha and his followers, who exclaim that the vase is perfect now. The systematics to reach enlightenment, is reminiscent of the therapy for variant symptoms with a panacea for every individual to achieve eternity. Despite his -usually implicit- presentation of universality, and despite the many valuable features that the Buddha denotes, he remains a sage who is time-bound and place-bound. He was a prince and he remains one by prescribing to everyone his newly formulated laws - in spite of himself he cannot deny his background. Furthermore, what the Buddha introduces is not new, but an in Siddhartha's eyes repaired and restored perfect Hinduism - though he does not say this. In addition, the Buddha indicates a substantial amount of assumptions about man, the qualities that are present in every person, but of which it is not determined in advance that these indeed cause the human suffering. The theory that Siddhartha was a mere figurehead in the power struggle between the monks and king Suddhodana is not investigated here -it is outside the topic-, though the reader of course is free to further this line of inquest. T he time of the Buddha was a time when man had not left behind the Neolithic that long ago -as the Middle Ages to today- with the Bronze Age even more recent+. The Aryan migrations were just past their peak and the Indian society -post Indus culture- had not or hardly stepped into the modern time. It was a time when learning and education was reserved for a select group, a time when global exploitation and slavery were included in the normal course of events, a time in which power relations were strict and wars brutal and gory. In the -rural areas of- hardly developed countries, this is still the case - thirty-six million people in slavery was the last published figure. Especially education for girls and young women is unsatisfactory or is non existent. Since the time of the Buddha humanity as a whole made many giant steps through improved training and education - though still far from ideal. Man usually no longer beats his fellow man with a mace on the skull, or drives him a sword through the heart. Yet now he sends drones and smart bombs and as a last resort a nuclear weapon could be detonated. The giant leaps in education have not focussed man less on the material. The essential difference between the time of the Buddha and the present day is that man is no longer vulnerable to the pedantic and will make great strides, is even creating them right now, towards a global awareness of what a person can and cannot inflict upon the other - less dependency on and attachment to the leader also means less war. In a time when people through education become more aware of their capabilities and thus their responsibilities patriarchs who speak wise words no longer fit. The wise words generally still deserve to be studied, yet the patriarchs are obsolete. The daily consequences of all that old wisdom are irrelevant to the present age, because the world that was their reference represents a bygone age - as a mandatory same day burial in an age of refrigerated morgues. What one observes today is that only a certain elite takes in the words of the Buddha - Hollywood stars, academics, and people who have lost their faith and now look for another place to hide, those who seek an excuse to turn their back to the world anyway. What one still does not observe is the general conviction of humanity that Buddhism represents the right way of seeing. Already in the day and age of the Buddha his teaching was in a sense a doctrine for the elite, a doctrine where people who had to toil for their daily bread had no time for.Buddhism nevertheless deserves to be carefully studied and not only by highly educated people. When this religious philosophy could be disembarrassed of its main drawbacks -being time and culture-bound as well as hierarchical- thoughts and considerations that are accessible to all and can be pondered by all may remain. That only would enrich the human collective global mind. That a person must conform to a template, a grid that each must be squeezed through, arouses not only aversion in the modern era, but all things considered also in ancient time. Every person learns in life and is aware of that at a certain moment in life -usually during the fourth decade- and then spends the time in the rest of life to grow into adulthood never attained when one submits to a specific doctrine or teacher - Buddhism so regarded even is counterproductive. Every person is quite capable to step in at some point on his inner road and from that point onward in an almost Gaudían way -as organic- become one with himself and grow forth. No one is served by 'obtained' wisdom because this demonstrates a still dependent mental bearing, a commitment to the Luciwher paradigm. Every person without exception is in his own way, at his own level and at his own pace very well capable to live his life with integrity - the bridge has been built a long time ago, but man has not yet a natural urge to cross. The wise elders may still have an important say as referent in what an honourable way of life is, but no longer as compelling authority. A modern person cannot allow anymore a 'saint' to prescribe anything from the outside, but develops from within his vision on how to live here with all the others. Or perhaps something like what the Buddha would say, "Religion does not consist in knowing the truth, but living it." The human is his own midpoint, and that does not need to be proven and that cannot be denied. The road for humankind is long, but not without end. Postscript

The impression could arise that

after reading this little essay on Buddhism you are implicitly asked to choose

for or against Buddhism. Well, nothing of the sort. You are mainly and

explicitly asked to think for yourself, as is always the goal the writer has in

his sight. The entire book is about the working of the Luciwher paradigm,

the mindset of all humans to gladly accept authority or alternatively be an

authority. In the view of the author this paradigm lies at the root of the

dysfunctional relationships people have and therefore is the basis for the

suffering in the world. If this diagnosis is correct than solving one's own

suffering stands paramount before one is ready to meet the world - when one is

not ready this meeting becomes a confrontation. When one is already on this

confrontational route, a person will get sicker and sicker in the course of life

- causing even more harm because of it. However, no one is beyond curing

provided one cures oneself, for no cure comes from outside or even above. The

only therapy+

comes from within, perhaps after consulting wise

words+, yet formulated by

oneself.

Notes to "The Prince and the pain of being"

1)

The "Majjhima patipada" is the term by which the Buddha denoted the Middle

way, the "magga" for short. The Buddha called magga the road that had

brought his suffering to an end, the way that involves a person to end his

suffering should avoid the extremes. One of the extremes relates to material

gratification. The Buddha called it sensual gratification, the gratification

of the senses. A path or attitude to life that he gave the term

Kamasukhalikanuyoga. The suffix in this term is yoga -a word directly

related to the word yoke- which means that immediate gratification of

material need requires effort. One can refrain from this specific effort.

The pursuit of material wealth in the time of Buddha was no different than

in the present time - only the products have changed. 2) See Book 5, chapter 2.1 and further, “The Heirs to the Veda” (right click). Back to the text = 3) Also in this variant of reincarnation an elitist judgment is hidden - still a princely character. The Buddha could clearly not imagine that the life of a simple farm labourer could end with what he called Parinibbana - that demonstrates little understanding of the inner life of the common man. Back to the text = 4) The three characteristics refer to the method by which the goods and objects in the world are present, the way one is conditioned, attached to the material world. The first characteristic is Annica, the impermanent, inconstant and changeable nature of material reality. The second characteristic of material reality is Dukkha, the fact that reality is painful, causes stress and discomfort and is uncomfortable. These two properties lead to the third characteristic, the Anatta, the fact that the characteristics by the manner in which they are experienced are not native to the human being and cannot therefore be considered as part of the self. Back to the text = 5) The Four Noble Truths are: there is suffering, suffering has a cause, the cause of suffering can be eliminated, by following the Eightfold Path the suffering is ended. Suffering is caused by three types of craving: sensual desire, desire for something that exists or should exist, desire for the end of something that exists or will exist. Suffering is eliminated by the Eightfold Path: the right views, the right intention, the right speech, the right action, the right way of living, the right effort, the right mindfulness, and the right concentration. Back to the text = 6) Kāma Rāga is also a natural herbal formula for penis enhancement that works on the body and mind to improve overall sexual health, increases libido, strengthens erections, improves ejaculation control, increases seminal output, and intensifies sexual pleasure and orgasms. Back to the text = 7) By Rupa Rāga is meant the desire for the high stages of meditation according to the four lower jhanas and with Arupa Rāga the desire for the high stages of meditation according to the four higher jhanas. With jhana the state is meant in which one resides when one meditates. Back to the text = |

Siddhartha indeed later considered him as an obstacle in achieving ultimate

spiritual happiness. Later in life Rāhula became a bhikkhu, a mendicant,

student and servant of the other monks.

Siddhartha indeed later considered him as an obstacle in achieving ultimate

spiritual happiness. Later in life Rāhula became a bhikkhu, a mendicant,

student and servant of the other monks. intentions of Siddhartha's father and Rāhula's grandfather, King Suddhodana.

After having sought the confrontation with his father, Rāhula then wanted

his recognition.

intentions of Siddhartha's father and Rāhula's grandfather, King Suddhodana.

After having sought the confrontation with his father, Rāhula then wanted

his recognition.